EDITORS’ LETTER: Issue 3…

As Peauxdunque Review emerges from the year of pandemic and protest and finds the world both changed fundamentally and still changing, we want to reflect back on our editors’ combined message from the heart of 2020, from our Issue 3:

Issue 3 of Peauxdunque Review comes at a time of extraordinary social upheaval. I’m aware this is no great revelation, but it bears contemplation. Life, or at least our concept of life prior to 2020, is no more. As COVID19 takes and takes, we grow weary, pulled in pieces in all regards. This fracture is profound, and it is numbing us. In the midst of this deep night, however, hope’s sparks float on the wind, gathering and catching, a change-radiance building in their wake. For the first time, calls for change, demands for true justice and equality are omnipresent. It’s an awakening long overdue.

For my own part, I grew up thinking I was too poor to be privileged, much less prejudiced. Deep down, though, I always knew the playing field wasn’t level. I just never said anything, maintaining that old herd immunity of ignorance. I’d like to blame the utter lack of honest historical education we receive in this country—Manifest Destiny, sea to shining sea, and all that. This white-washed façade promoted a population raised to believe the myths we were told about ourselves, about how the country was settled and built, rather than accounting for the dark truths. Sure, we had our thirty minutes a day of social studies: Trail of Tears, slavery, the Civil War, Lincoln, Dr. King, reservations, desegregation—but all as past-tense stuff, so as to avoid any of that pesky cognitive dissonance in the populace. And on we went with our self-delusion: Bad things happened; we changed them; we got better; that’s all in the past now. Except the past never went away, neither for those crushed beneath it nor for those doing the crushing. Not for those asphyxiated by a system set up to deny anything is wrong. And this trumped-up reality has allowed a sickness to build, a malaise that, until recently, the dominating sectors of society seemed happy to deny and ignore. But no more.

The times scream for change, and we at Peauxdunque Review choose to add voices to the chorus, for it has never been more necessary to speak with many voices while acknowledging each individual refrain. On that note, I have asked members of our editorial review board to weigh in on this moment, as well. Here are their urgent words.

Larry Wormington

Editor-in-Chief

Peauxdunque Review

Maurice Carlos Ruffin, Editorial Review Board:

We are the witnesses. The old normal is dissolving into something new and hopefully better. The work of the poet and the writer is to engage with our community and reflect what we see. One day, the people who come after us will want to know what this was. Our work will tell them.

J.Ed. Marston, Features Editor/Asst. Poetry Editor:

Since the COVID crisis started, writing has felt like working as an air-traffic controller at Airport Armageddon in the middle of a sandstorm. First off, the word “controller” in this job title is completely off-base. Like my counterparts in aviation, I have control over absolutely zilch. All I can do is write messages that might cut through the static and hope my work is good enough to help my readers find their own way through.

My local backdrop in Chattanooga wedged devastating tornados between the onset of the pandemic and the continuing civil rights protests in response to George Floyd’s murder. I’m very fortunate to have a day job that afforded me opportunities to write actionable ephemera about all of these huge of-the-moment events. I’ve also made progress on my personal writing projects. But, up here in the so-called control tower, the radar is down. Visibility is zero. I speak painstakingly assembled words only to hear them swept away in the frenzy and static with no way to tell if they made any difference. And, when it comes to my personal writings, I’m speaking into a dead microphone, accumulating words that might not ever matter enough for publication.

So, why should I bother? Why should you? The only thing I can say is that I have an intuition that’s been reinforced by my writing experiences. The only way to win the game is to keep playing. Whether something is a tragedy or a triumph depends on when you cut the scene and how long you let it run. In the midst of a tragedy, the only way to get to triumph is to keep writing.

Emily Choate, Fiction Editor:

Every age is an age of paradox. Every new era has been born of relentless, dazzling, unforgiving change. As storytellers and poets, we have always been called to attune ourselves to the present moment. We have been called to bring forth what has been hidden from view—from our villages, our families, ourselves. Especially from ourselves.

Attuning ourselves to this Rubicon age, irrevocable and impersonal in its trample through our lives, requires exceptional humility. Our dominance-fueled culture scorns humility as weakness, yet it may be the single most spiritually useful condition available to us. When we must fight for one another’s survival, humility becomes the source of electrifying strength. As we now grieve, as we rage, as we undeceive ourselves of illusion after illusion, it is through humility that we surrender to our fundamental interconnectivity.

We have been called to receive this moment, alive and alert to our purpose like never before. In these first months of pandemic, protest, and deep reckoning, we have been readying ourselves for the visions that can only arrive during the kind of profound transformation that cannot be undone. Because retreating into the past is no longer possible. Rather than clinging to the old reference points, even as they collapse around us, we have been called to drop the deadweight of our illusions, so that we can travel light, toward a future that we cannot yet imagine.

Freed from that weight, we have also been stretching ourselves, becoming vessels that will be able to receive new stories—the stories that could only come to us now. To bring them into form is our holy purpose.

April Blevins Pejic, Creative Nonfiction Editor:

On the second day of the quarantine in New Orleans, I walked the empty streets of my neighborhood. Normally the Marigny and French Quarter are teeming with life: musicians busking on corners, bartenders serving cocktails, psychics selling a glimpse of the future, and tourists crowding sidewalks as they gawk at the spectacle of it all or snap photos of themselves against the backdrop of the historic architecture.

But on this day, the only other living thing I saw was a raccoon. I’m no wildlife expert, but I do know that a daytime raccoon is probably a sick raccoon. I stopped to watch him. He stopped to watch me. We eyed each other warily and kept our distance as we shuffled away from each other.

As the days in quarantine dragged into months, I continued taking these daily walks around the deserted streets. Sometimes, I saw a few other people out for fresh air. While these strangers and I might nod hellos, we gave each other the same vigilant distance that I kept with that sick raccoon. We kept this distance out of love, out of a desire to keep our community safe even though walking across the street to avoid other people is completely anathema to who we are in New Orleans.

That’s one reason I’m so excited to publish Ben Aleshire’s “Love for Sale” in this issue. This essay, the winner of the CNF category of the 2019 Words and Music Writing Competition, calls out across the distance from a time before empty streets and boarded-up bars, a swan song to life before global pandemics and overwhelmed hospitals. While the imagery of busy French Quarter streets makes me nostalgic, the insight in his words rings even more true now, “… love is what wheels us through a dying world that doesn’t make sense.” Love, indeed.

Nordette Adams, Poetry Editor:

And so we have been hit on every side in 2020: We wait out a pandemic, hear of overflowing morgues, and watch or walk with the inevitable rage racism produces. We witness as well the highest unemployment rates since the Great Depression. In New Orleans, we gaze at the Gulf, and pray that the gods of hurricanes will be kind this summer for we, like the rest of the world, have had enough loss. So far, no one in my family has died during this crisis, but I sense the city’s unease and sorrow, knowing Death is not done. A friend, a gifted educator, succumbed to COVID-19 in April. I have seen three neighbors taken away in ambulances and talked to friends whose loved ones have died. In isolation, I have been writing away anxiety and seeking the work of others. Reading literature is the closest we may come to entering the minds of fellow humans. In stories and poetry, we see that we are not the first to think terrible things, to fear our present and our future, to face grief during a tumultuous era. We perceive then that our bodies may be isolated but our spirits are not. For our readers, I hope some passage in the Peauxdunque Review evokes that sense of belonging to a greater collective, broadens perspective, and awakens empathy for those who seem very different from them. This is literature’s promise and magic. Without recognition that we are part of the world, without the ability to feel what others feel, how will we ever salvage health and peace from devastating turmoil? How will ever overcome the sharp division that remains?

Tad Bartlett, Managing Editor:

In the grand scheme of things, I haven’t been alive too long. Forty-eight years. But I don’t think I’ve seen a world as much on the verge of something horrible or something beautiful as we are seeing now. When I was a kid, growing up an outsider in my own podunk town of Selma, Alabama, I knew and saw racism and white supremacy early and often. Often we marched or picketed or spoke, but seldom did change come. Since then, in our social-media-amplified world, we have seen an endless procession of murders of Black men, women, and children, at the hands of racists and white supremacists and often the police, followed by a cycle of protest, promises often empty, and a subsidence back into the comforts of always doing what we’ve always done. But this time, this year, feels different, following the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and too many more, as protests did not subside but magnified, as each city lent its own flavor to its collective shoulder on the wheel. This time feels like it is different, that we will not sink back into the muck, and maybe it feels different because the world is willing it so, is stating clearly that it shall not be so. The urgency of the words and language of our time is shining through.

And maybe the words are so urgent now, not just because the cycle has spun around too many times, not just because we are all sick and tired of being sick and tired, of our brothers and sisters having their humanity—and thereby all of our humanity shared in common with them—denied, but also in the face of pandemic, of widespread reminders of the precariousness of life itself and how we live it. There is no comfortable place into which to retreat. All is upheaval. The need for clear words, for stories and narratives and rhythms about how to live as people among people, has never been more urgent.

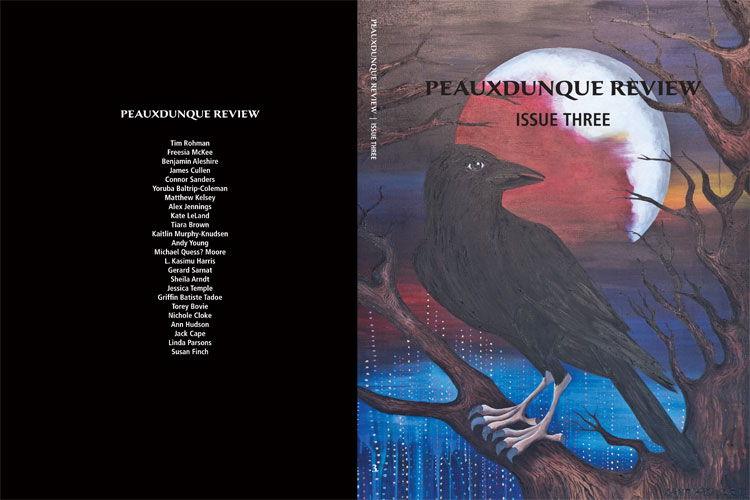

And it is the gale of this moment that has blown the ship of Issue 3 of Peauxdunque Review to the shores of now. This is our annual competition issue, where we publish the winners and runners-up and selected honorable mentions from the previous year’s competition alongside the cream of the regular submissions that writers send our way. We are tremendously proud to be a home for all of this good work, though perhaps never prouder than we are of the Beyond the Bars category, a no-fee category for incarcerated juveniles nationwide, a category that puts faces and words and, ultimately, humanity, onto a segment of our society too often abstracted into an invisible collective mass. We see you. Not just our published winner and runner-up, Connor Sanders and Griffin Batiste Tadoe, but all of you. That is what words—your words, our words—do. They help us see each other. And in this vein, we are very glad to feature the prose-poem of Michael “Quess?” Moore, a New Orleans poet and educator, who is also one of the co-founders of Take ‘Em Down NOLA, a group formed to bring down white supremacist monuments of all kinds in New Orleans and also one of the prime drivers of this summer’s protests in New Orleans. Quess’s “on the flames in my bones and how they got there” speaks directly and with immediacy to our current moment. And immediately following Quess’s work we are honored to present selections from the incredible series of photographs from L. Kasimu Harris’s “War on the Benighted,” which has been exhibited in several museums and written up in the New York Times. Kasimu’s photography mixes documentary work and staged narrative work to tell the stories of our injustices and our empowerment; “War on the Benighted” tells both stories simultaneously. We are gratified that our pages could be a home for these words and images, and for so many important and urgent words and images in this issue. Thank you, readers, for sharing in them with the writers and artists and with us. We see you.